Branch per Story Pattern and TFS

The TFS branching guide is a very detailed run through of the various situations and scenarios under which branching can be performed and the different strategies that exist, however because the guide covers so many scenarios it’s difficult for some people to know what approach they should follow, and when they look at some of the advanced diagrams they freak out at the complexity.

For this post I’m going to keep it simple and just show one approach, the one that I feel is best for agile teams implementing using user stories. It’s effectively the feature branch approach, and I’ve been tempted not to write this post, however I find that that feature-branch approach can be a little confusing for some people. “What is a feature?” “Is it multiple stories?” “Is it an epic?” “Is it a bug fix?” “Should a feature live across multiple sprints?” These are all questions I hear and it’s probably because the terminology is a little too generic and becomes open to interpretation and thus misunderstanding. So, let’s make it easy and use Agile terminology.

Why Story Branches

So before we get into it, what exactly is wrong with working in trunk or using a branch per sprint approach? If you can make it work then there is nothing wrong with that approach, but it does come with some with hidden dangers.

Consider the following situation. A team accepts 3 product backlog items for a sprint and only completes 2 of those items. The third story was in progress when the sprint concluded but was far from complete and the team now has a section of unfinished code in their code base.

What should the team do with that unfinished code? Should they go back and comment it out or delete it? Maybe, but how will they be sure they got it all? What if some of the changes they were making affected the system architecture and those changes had been used in the implementation of the other two stories? What if the code was also merged to another branch in preparation for a release?

What if they take a different approach and try wrapping all changes in if-blocks during development to try and isolate the changes? Sure, this can work. But again it has challenges. The team needs to maintain a set of variables or pre-processor tokens related to each item that are used to decide if a feature is available or not. There’s also going to be a large number of if statements that will add noise to the code and in a complex system you can easily imagine how out of control this could get.

What if they just ignore these challenges (or forget the code) and leave the unfinished code as is? At best they have code that is unused and simply adds bloat to the system, at worst it results in the system being released with broken functionality and open security attack vectors that have never been checked or tested.

If we also remind ourselves that sprints should produce production ready, potentially releasable increments of the system, then we really, really don’t want to have work in progress code in the system at sprint conclusion.

For all of these reasons we should ensure our development of a feature is isolated from the rest of the development team and only made generally available when complete and ready for integration testing.

There’s an interesting side effect to taking this approach. If we develop features in isolation and consider Conway’s law which when paraphrased says that system architectures reflect the way the organisation communicates, then by nature the systems we develop using a branch per story model will likely be architected and designed as componentised and modular systems, mirroring the development approach we are using.

Downsides

What are the downsides, then? Surely the administration overhead goes up and chances of screwing up merges increases, and yes, there is an element of that, but it isn’t as bad as you think.

Administration time goes up because we now have to remember to create a branch, and we have to remember to switch branches when we work on different stories in the same sprint. Is this really an issue though? Maybe it is. However maybe it’s a hidden blessing in disguise. When working in an agile manner we want to minimise wasted effort and keep our work in progress as low as we can. We know that the costs of multi-tasking, working on different stories at the same time, means we’re go slower overall than if we just work on one story at a time because of the mental context switch and yet the temptation to multi-task is high, especially if the stories we work on are somewhat boring.

By following a branch per story strategy we discourage ourselves from multitasking since the simple annoyance of switching to a solution file on a different branch gives us a natural prevention mechanism. Note that this annoyance doesn’t work with DVCS systems like git and mercurial since branch switching is very quick and easy, but in TFS, SubVersion and similar branches are represented as folders and switching means swapping folders, and thus closing and re-opening the solution.

What about merging? Branching is easy but a great deal of pain can be had in the merging of branches. This pain is most often encountered when the two branches have diverged significantly. However, in a branch-per-story model most branches are short lived and thus merging fairly straightforward. It doesn’t mean merge conflicts can’t occur, just that the merges are likely to have small amounts of conflicts.

Visual Branching Model

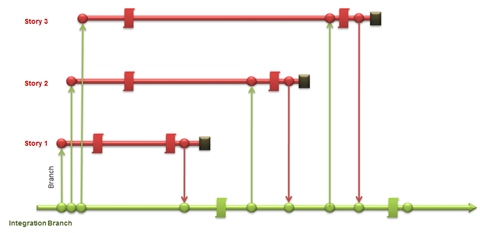

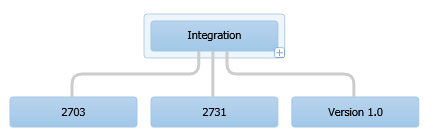

So let’s have a look at what we’re doing with the branching model. For each story in the sprint we work on we’re create a story branch by branching the main integration branch.

Let’s say the team picks up three stories for the sprint. We create the story branches and the team commences work:

Let’s say Story 1 gets completed first. The code for story 1 is merged back to the integration branch, the integration code is checked and verified and when all the tasks for the story are complete the branch is killed off.

Next, Story 2 is completed so the developers pull from the integration branch, merge the changes, confirm things are OK locally, then push their changes back to the integration branch. Again, the developers check the code in the integration branch is OK, and when it is the story 2 branch is killed off.

Finally Story 3 is code complete. Again, the developers pull the branch code down to their story branch, do the merge and make sure it’s OK. When it looks good they push their changes back to the integration branch, make sure the integration branch is OK and kill of the Story 3 branch.

Pretty simple process, right?

Doing it with TFS

So, enough with the explanations let’s see how we do this with TFS.

Creating branches is easy enough, but how do you name the branches? We don’t want to try and embed the story name in the branch name since that will increase folder length and makes it far more likely that we’ll hit the file path length limit (yes, there is one and it’s smaller than you think).

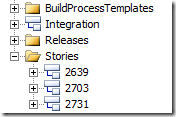

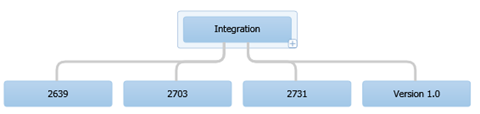

The strategy I prefer is simple. Because we are using TFS and stories are just TFS work items, I like to use the story number as the branch name. Here’s an example:

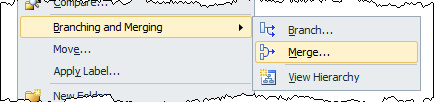

Now let’s do some work on story 2639 (aka “Make this system more awesome!”) and check it in. Now we need to make sure that we’re on par with the integration branch by doing a merge. We simply right click the Integration branch and select Merge:

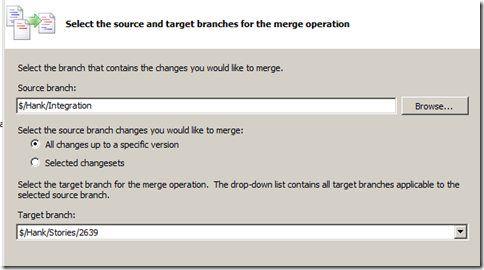

Then merge to the appropriate story branch

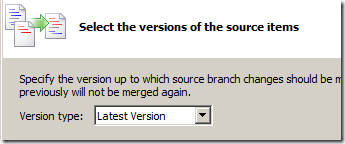

Select the latest version to make sure we’re current and hit the button

It appears there are no changes to merge. Excellent, we’re current.

So now we merge our changes from the story to the integration branch (same process, just start by right-clicking the story branch). Also, don’t forget that merges are made as local changes and still have to be committed, so add a check in comment and do just that.

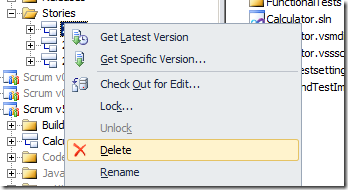

Wait for the integration build to pass and check the acceptance tests pass to let us know that the story is complete. Once it is we can now kill the story branch. To do this, simply right click the branch in source control explorer and select delete!

Again the delete’s are pending changes until we check them in. So again, add a comment and check in the changes.

Our branch hierarchy now changes from this:

to this:

Nice and simple. And not a lot of overhead.

As for the other stories we follow the exact same procedure when they are complete:

1. Make the changes needed for the story in the story branch

2. Pull and merge changes from the integration branch into the story branch

3. Deal with any merge conflicts

4. Check that the story is still OK

5. Push and merge the changes back up to the integration branch. You shouldn’t have any merge conflicts for this merge.

6. Check that the Continuous Integration build passes

7. Run any other tests on the integrated code as required.

And we’re done!

When all stories are complete in the sprint there should be no story branches left. The only time this won’t be true is when the team finished the sprint with incomplete stories.

What About Bugs?

Bugs in an agile team are just the same as stories. Create a bug fix branch each time you need to fix a bug just the same as we do for stories.

About the only time you might not do this is when you are doing really simple bug fixes such as spelling mistakes where the changes are just cosmetic and there are no real logic or functional changes.

What About the Build Server?

So a question you may have is what do we do with builds and the build server? Answer: it’s up to you. Given how short lived the story branches are likely to be it’s probably not worth creating build definitions for each story, but again, it’s completely up to you. Regardless of wether you have a build per story or not, you should have a continuous integration build tied to the integration branch. When each story is complete and merged back to the integration branch a build should be triggered that compiles the code, runs all the unit tests and so forth to confirm that the code in the integration branch is OK and nothing went wrong during the merge.